Cumberland Lodge Fellow 2022-24, Meaghan Malloy, reflects on using her Personal Development Grant (offered as part of the Cumberland Lodge Fellowship) and what she learned about exercising her voice and contributing to social change from Central American youth through art

I am not artistic. I have no hidden musical talents. I cannot paint, sculpt, or draw anything of worth. So I never imagined that one day I would be involved with arranging an art exhibition with 11 young people from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, exploring their experiences and opportunities to contribute to social change in their communities.

My journey to this art project began several years ago when I was working as an education and development consultant for international organisations and nonprofits. As a privileged White woman from the USA, with several university degrees, I started to critically reflect on the role I was playing (or not) to address social conditions in communities and countries whose experiences were very different to the ones I knew. Through my work with different international organisations, I found myself in headquarter offices, with people from different countries, operating in a global culture with a particular language and mode of conduct that felt disconnected from the communities and people we sought to serve. I worked on projects with specific goals to equip young people with knowledge and skills to “build a better world”, but at the same time I was questioning my own position in this work, unsure of my abilities to effect social change, let alone how to support others to do so.

My concerns with development aid only intensified as the global COVID-19 pandemic heightened the visibility of structural inequalities around the world. To mitigate the effects of COVID-19, global directives pointed country teams to digital learning, handwashing and vaccines; their messages came back saying how the communities they work in have no internet, limited access to water, and that medical professionals have not visited in two years to do routine health checkups or administer any vaccines. At the same time, I witnessed members of my government, the US government, downplay the severity of the virus, create bidding wars for medical supplies, and allow vaccine stockpiles to expire. I watched all of this knowing I was benefiting from my White privilege, as someone with access to the internet, water and timely vaccines. I was implicated in these systems of inequalities, but felt hopeless around how I could contribute to dismantling some of these structures of power, privilege and oppression. I felt that my White, American presence in development work was potentially creating more harm than good.

One option was to leave the development sector altogether, but this felt like an avoidance tactic, an easy option to sidestep any real accountability. When I raised my concerns with trusted colleagues, they explained that it is important to have someone like me to talk to, someone who is reflecting on some of these structures of inequality. While this response offered some personal comfort, I wondered if that was all it was, colleagues being kind to me, and if that was a reason to stay.

Grappling with these questions, I opted for a third way. I started a PhD study (which I fully acknowledge is another form of my privilege) to further reflect on development aid, drawing from my prior experiences working on aid-funded projects for youth in Central America. My study is investigating how global education policy concerned with developing youth agents of social change is understood, interpreted, or contested, by youth and those that work with youth in and around schools in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. This research seeks to explore the similarities and differences between global and local perspectives, and how these may contribute to reinforcing or dismantling structural inequalities and processes of social change within and across the three countries.

Through conducting my study, I learned about participatory approaches for involving youth in social inquiry about complex social relations, structures of power and oppression, and how privilege can produce and sustain social injustice. “Photovoice” has emerged as a methodology to engage youth, through photography and other art forms, in a process that develops their capacities to record and critically reflect on important issues to them, individually and in groups. The art can then be used to promote critical dialogue in communities and to reach policymakers.

To deepen my knowledge of these processes, I applied for the Cumberland Lodge Fellowship Personal Development Grant to explore ways of working together with youth through Photovoice, and how this methodology may resonate with young people in Central America.

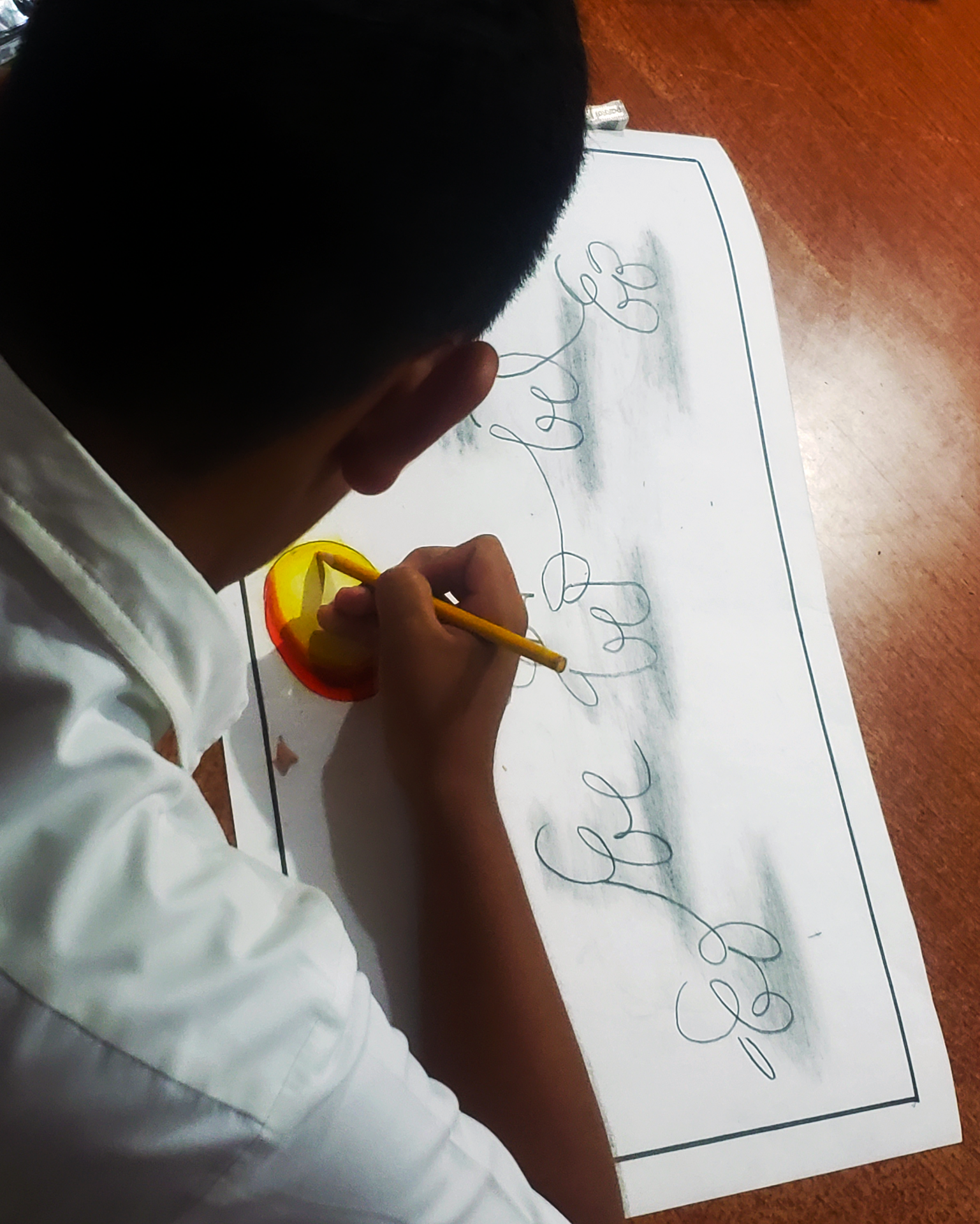

From June to July 2023, 11 young people working with me took photos and created other artworks around the prompt: “situations where young people are exercising agency, voice and action for social change, or moments where these aspects may be restricted”. Besides this general prompt and safeguarding protocols, instruction was minimal to encourage each young person to reflect on the themes and how they resonate, or not, in their life. In the end, the young people created 92 original pieces of artwork (89 photos, two poems and one song). In August 2023, through collaborative discussions over Zoom, they selected 18 artworks (16 photos and two poems) for their public art exhibition, Somos Un Cambio, Somos Una Voz, depicting the various ways youth in Central America contribute to building a better world.

The images and artwork created by the young people deeply resonated with me. What I observed is that all of us – despite our different backgrounds, social identities, experiences, locations, and cultures – are grappling with similar questions about our positions in society, how to relate to others, and the roles we play in processes of social change. In our final discussion together, one girl from Guatemala spoke about navigating her choices, and how getting up and going to school is an example of positive youth action when the alternatives could be getting involved in gangs and violence. A boy from Honduras spoke about navigating his environment, learning how to recognise problems around him and how he can help address them, which could be assisting a friend with his homework or planting trees to protect the environment. A girl from El Salvador spoke about navigating her emotions and having the courage to speak out because “art can unite us, thinking can unite us, social problems can unite us” and so not speaking out can divide us.

The power of this exhibition is in the hands of the young people. I simply supplied cameras, coordinated meeting times, and organised the printing of the exhibition. The vision, design, and art of this exhibition is completely credited to the young people involved. By shifting my position from speaking to listening, I recognised that I too am getting up each day, putting one foot in front of the other, and trying to navigate my choices, environments and emotions the best ways I know how. But I am not nearly as brave as them. I have not always spoken up or called out injustices publicly for fear of how it might harm my career, my reputation, or in another word, my privilege. Throughout this project, I learned how internally grappling with my concerns and not finding spaces to have these conversations is contributing to social division.

I am grateful to the Lodge for supporting this exploratory art project and providing an opportunity for deep personal reflection. I am also grateful for the space to have this tough conversation about my power and privilege as I explore ways of being more accountable. Lilla Watson, an academic, visual artist and activist for women’s and Aboriginal rights, said: ‘If you have come to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you are here because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.’ This quote speaks to the experience of this project, but I know this work is just starting for me. I am not perfect, and I will continue to make mistakes, but I have seen how an arts-based project built on mutual trust, respect and listening can generate and signal new ways of working together, and like me, you can be part of it – no art skills required.

The art exhibition, Somos Un Cambio, Somos Una Voz was exhibited in Parque Cuscatlán, San Salvador, El Salvador (October 2023), IOE Library, London, United Kingdom (December 2023- January 2024) and will soon travel to Cumberland Lodge, Windsor, United Kingdom. For more information, please see: https://www.meaghanmalloy.com/artexhibition