What will the UK’s faith and belief landscape look like in 2040? What are the ongoing trends? What social, economic or political factors are likely to influence these trends over the next 20 years? And what are the challenges and opportunities that this changing landscape brings?

These were the major questions that opened the first of four sessions of the Faith and Belief 2040 virtual conference, hosted by Cumberland Lodge in November 2020, in partnership with The Faith & Belief Forum and Humanists UK. This blog focuses on the opening session, which introduced some of the major issues around diversity and identity in the UK today, by exploring the key transformations taking place in our faith and belief communities.

The conference started with opening remarks from Dr Ed Newell (Cumberland Lodge Chief Executive), to welcome everyone, provide some background to Cumberland Lodge, and introduce the guest panellists:

- Andrew Copson – Chief Executive, Humanists UK

- Professor Linda Woodhead – Distinguished Professor of Sociology of Religion, Lancaster University.

This session proceeded with brief presentations from the guest panellists and a breakout session to reflect on what we had learnt and to brainstorm ideas with fellow participants.

Non-religious identity and humanist beliefs

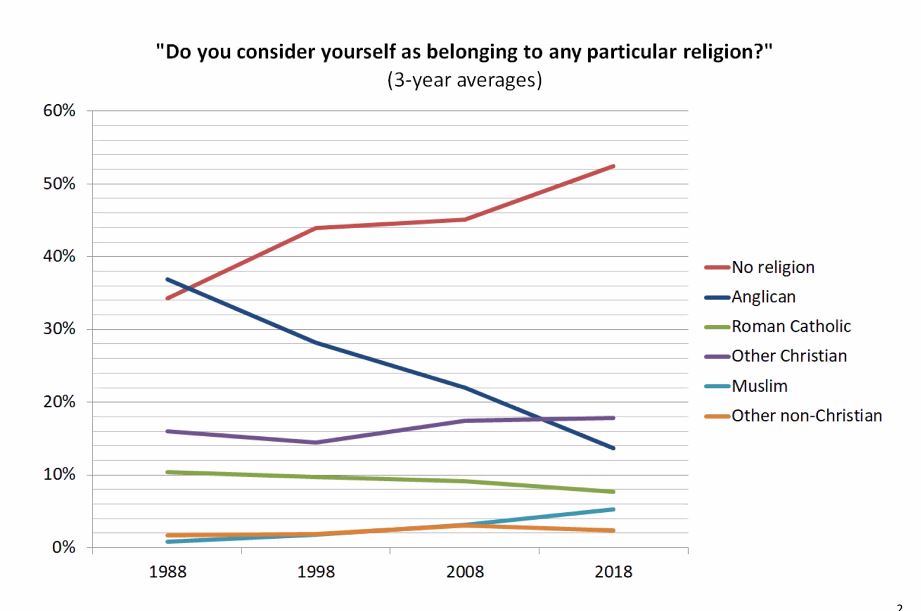

One of the speakers explored the growth in non-religious identity and humanist beliefs, highlighting data from the British Social Attitude survey of 2018, which showed steady growth in the ‘non-religious’ self-identification, from about 34% in 1988 to about 51% of the British population in 2018, with a younger overall age-profile than religious categories of identification. This showed us how rapidly the non-religious population is growing.

Our discussion explored this generational nature of the non-religious population and the effect of parents’ religiosity on their children, which showed that two non-religious parents typically produce a non-religious descendant whilst two religious parents have a 50% chance of producing a non-religious descendant. Also, a single religious parent is more likely to produce a non-religious descendant.

With this ongoing trend alone, we may reach 60% non-religious identities in the UK by 2040, which is likely to significantly influence the social fabric.

Bearing in mind that our religion not only influences our identity but also our beliefs, the non-religious population largely tends towards humanist beliefs – applying a rationalist outlook of thought that attaches prime importance to human rather than divine or supernatural matters. Older people often have a range of both religious and humanist beliefs, whilst younger people tend to have a more comprehensively non-religious humanist belief.

With the help of a range of graphs and data, this speaker concluded that there is a trend towards non-religious and humanist beliefs in the UK, and over the next two decades we will see a further decline in Anglicanism – the state religion – alongside the growth of other religions and non-religious sentiment.

Ethnic diversity and tolerance

The data also revealed that 60% of people of white origin are non-religious, whilst 80% of non-white Britons identify with a religion.

Thus, as ethnic diversity increases, there may be an increasing divide in religious identities and beliefs. For example, a metropolitan and culturally diverse city like London will probably have a more religious population than other parts of the country.

The speaker highlighted that the non-religious tend to be more tolerant of people from a different religion or, for example, with a very different religious view of marriage. This point struck me because I feel that the rationalist outlook and humanist beliefs of the non-religious tend to pay more attention to the quality of character and the personality of individuals rather than their ethnicity or religious beliefs.

Perhaps this tolerance and acceptance will lead to a less judgemental society, that allows for mutual respect and cohesion, maintains our social bonds and resolves some of the polarising problems that cut across diverse ethnic backgrounds and beliefs.

The influence of trust in science

One of the speakers explained another key finding from the British Social Attitude survey of 2018, which revealed that non-religious people are more likely to disagree with the idea that we trust too much in science and not enough in religious faith, than those who identify with Christianity and or other religions.

Given that an increasing proportion of society is non-religious, this got me thinking that perhaps this strengthening of confidence in science will become an underpinning factor behind individual and collective decision-making, over the next 20 years and beyond.

Christianity ceases to be normative

This discussion opened up a whole new line of debate around the potential impacts of these transformations on wider society. If Christianity is declining, what is taking its place? What are the alternative forms of spirituality that are emerging?

Also, where do our organisational values come from and what are they referencing, and where might they come from in the future? The Christian work ethic is focused on sacrifice, but what is the focus of the non-Christian ethic?

And if Christian rituals are gradually disappearing, what is replacing them? Since there is a general decline in the belief in one God, what, then, is the new belief?

These questions set the tone of the second speaker’s presentation, which focused on the declining normative nature of Christianity in the UK – exploring the values, rituals and beliefs of British social-cultural life.

This speaker explained that, whilst Christianity has traditionally enjoyed moral primacy and been the moral reference-point for what most people and organisations do in the UK, an alternative ‘live your life’ ethic, which involves a sensitive discovery of who you are, making the most of your life and supporting others to do the same, is now gradually replacing the sacrificial Christian ethic. Our shared rituals are beginning to reflect this as well.

The speaker also mentioned that, alongside the decline of the belief in one God – the supreme Almighty God – we are increasingly seeing belief in various different gods and sacred beings, or ‘multiple forms of paganism’.

The cultural centre and periphery of the UK’s faith and belief landscape is shifting from a pattern of the Christian majority and various monotheistic minorities, towards a ‘no religion’ majority with diverse ‘alternative’ minorities.

Common themes from the breakout session

During the breakout session, we had rich discussions across five different groups, reflecting on the presentations we had heard.

Collectively, we came up with the following ideas and reflections, including a number of new questions that need addressing:

- Religion is becoming more individualistic.

- The idea of belonging and dealing with loneliness in the latter part of life is a challenge to look out for, as our faith and belief landscape changes.

- The problem of loneliness and the rise of the non-religious raises the question: what structures are in place to replace the care and support that the church has traditionally provided? Perhaps, digital communities – supported by apps and platforms that help to build cohesion in cities and neighbourhoods – could serve as an alternative to the community the church provides and help to bridge the loneliness gap.

- How do non-religious beliefs influence societal values and practices – from our festivals to our welfare systems and community engagement levels?

- Will there be a decline in the engagement levels of different care and support activities that come from faith-based social actions and volunteering outlets, due to an increase in non-religious sentiment?

- How might we adapt to these new trends, navigating them positively and constructively?

- What is responsible for the intergenerational differences in patterns of religious or non-religious identification? What is driving it?

- What will happen to the physical infrastructure of the community church, and how could church buildings be used in ways that support social cohesion in more religiously diverse societies?

- The rise of the non-religious: what will be the effect on schools, education and the curriculum? Should the curriculum change to reflect new faith and belief realities, and if so, how?

- Does gender have a role to play in this growing trend?

- What impact will the COVID-19 pandemic have on people’s faith and beliefs?

Concluding thoughts

The rich discussion during this conference birthed a new level of curiosity in me. The UK is one of the least religious countries in the world, and yet, one of the most Christian states in the world, and the only democracy to have religious seats in parliament. Seeing how the religious identity of the UK, as a Christian country, is gradually changing, I started thinking about what the impact of this might be, on leadership and governance, education and the curriculum, economics and trade, laws and policies, values and social norms, culture and traditions.

As a Christian, this session left me with more questions to constantly reflect upon, and reinforced my desire to explore diverse ethnic backgrounds and understand the influence of our religious diversity on our personalities and cultures, whilst appreciating the value of our uniqueness.