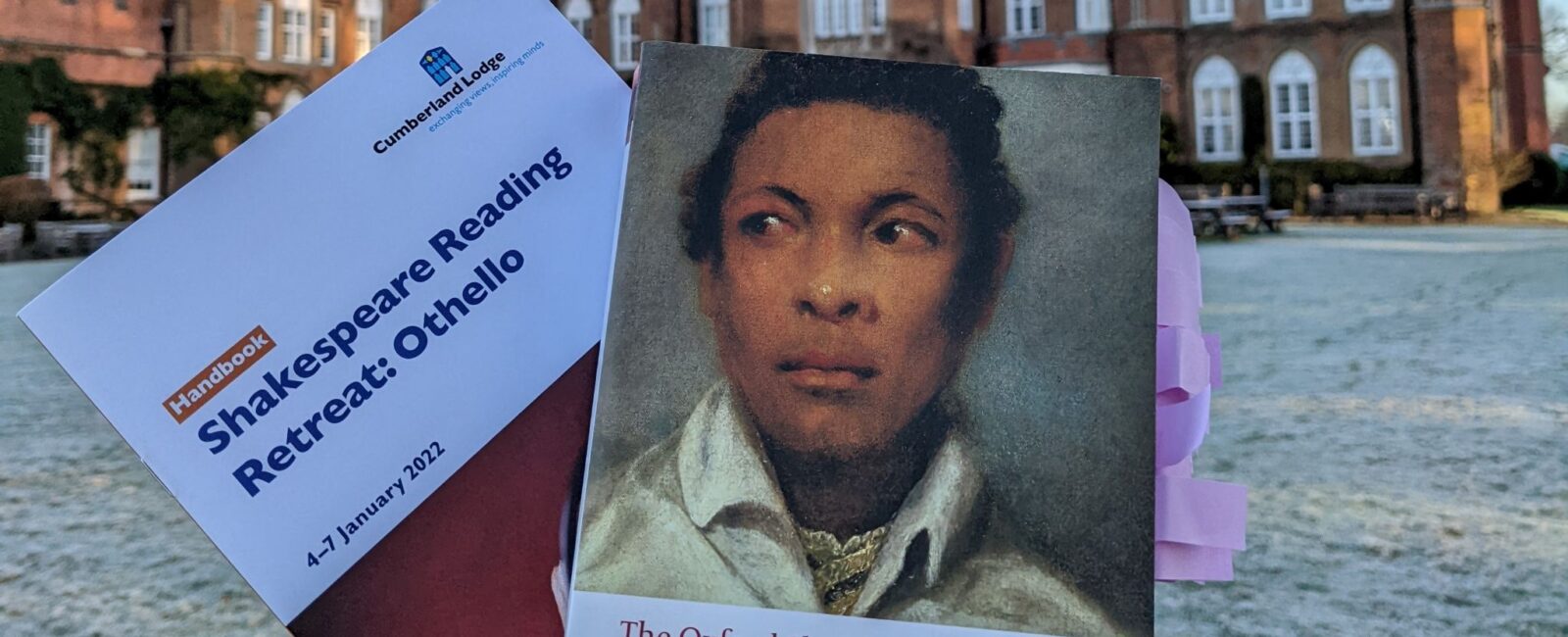

The Shakespeare reading retreat brings together Shakespeare experts, from academics to actors, and keen amateurs with a love of Shakespeare, to discuss one play over a four-day event. This year’s play was Othello; the retreat included film showings, study groups led by experts, and lectures with Q&A sessions.

Professor Sir Stanley Wells and Revd Dr Paul Edmondson opened the event with an overview of the narrative and themes which constitute Othello’s DNA. This discussion sowed thematic seeds relating to race, gender, and truth, which were harvested throughout the retreat. Both Stanley and Paul have a masterly knowledge of Shakespeare’s writings, his historical context, as well as an encyclopaedic familiarity with past productions.

At times it felt as though Shakespeare, the man, was an old friend of theirs and they tapped into a personal archive of past conversations with him and his contemporaries. However, this was only the beginning of the retreat and, to paraphrase Iago, the play’s protagonist, there were still “many events in the womb of time ready to be delivered”.

Trevor Nunn’s film adaptation of Othello (1990) was shown after breakfast on Wednesday. This enabled a visualisation of Othello’s central themes which are often considered to include race, gender, and class. This prepared everyone well for Dr Rowan Williams’s percipient lecture on the overarching role of power relations in Othello.

For Williams, at the centre of the play is the claustrophobic feeling that power is being enacted upon you but concurrently having a frustrating inability to comprehend how it is being imposed, or from which direction. This is most clearly demonstrated in the play through Othello’s relationship with Iago. Blind to Iago’s deceitful motivations, he places his trust in him. Iago’s manipulation of Othello is made possible through a clandestine power structure he has created through his lies; he is playing a different game, with different rules, to the rest of the characters.

Thursday saw Professor Tiffany Stern give a fascinating talk on Elizabethan material culture and how it could relate to the audience of Shakespeare’s play. By examining penny broadsheets thatcontained popular ballads, Tiffany was able to construct a deeper understanding of the experience of Elizabethan theatregoers when watching Othello. It was a reminder of the everyday differences between Shakespeare’s time and now, and goes some way in explaining why, so often, performances of Shakespeare plays tell us more about the society in which they were produced and performed than the one in which they were written.

Following this, Professor Daniel Grimley presented an absorbing exploration of Verdi’s process in writing the opera Otello (1887). Converting Othello into the medium of opera necessitated substantial modifications; these changes, again, tell us much more about Verdi’s Italy than Shakespeare’s England.

The final session on Friday saw Dr Amanda Piesse, who was erudite in study groups and hilarious at the dinner table, interview Andrew French about his life and career as an actor. Andrew recalled the significance of his mother instilling into him the importance of Shakespeare and how that has guided his career. Andrew also spoke movingly of his personal and long-term relationship with Stanley Wells who gave him the gift of belief at a moment when he most needed it.

It was wonderful to have an actor present for the full week who has played both Othello and Iago; his insights were always thoughtful and thought-provoking. I was lucky enough to play ping pong one evening with Andrew and a few of the other attendees in the Cumberland Lodge Vaults. Andrew and I were fairly hapless partners in a doubles match. When I declared that I wanted a different ping pong partner, Andrew responded to me with the suitably Shakespearean “Et tu, Brute?”.

Personally, the retreat gave me the opportunity to truly connect with Shakespeare, probably for the first time in my life, through an intensive study of one of his plays. The chance to exchange thoughts and ideas with leading academics, theologians, and actors, as well as a variety of other attendees, all associated through a love of Shakespeare was truly a privilege. It has undoubtedly had an effect on the way I think about language, literary interpretation, and The Bard more broadly.

Additionally, myself and the other Cumberland Fellows who attended the retreat, Hannah, Henna and Ellen, found the intergenerational conversations about narratives, race, and gender illuminating and sometimes challenging. I think they would share my sentiment that we all feel richer for the experience, and we hope that our presence was reciprocally enriching for the many returning lovers of Shakespeare.