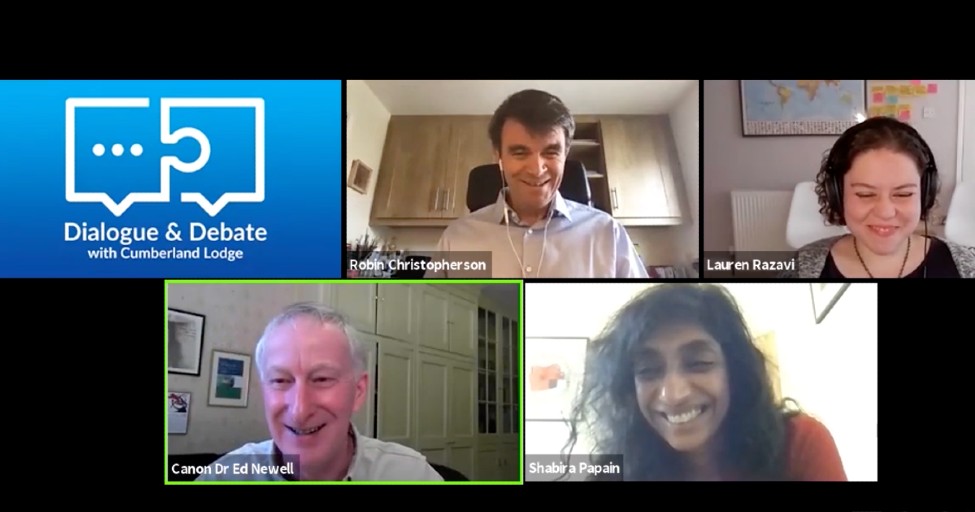

On Wednesday 5 August 2020, Cumberland Lodge hosted a live, interactive webinar on ‘COVID-19 & the Digital Divide’, as part of the Dialogue & Debate series.

Chief Executive of Cumberland Lodge, Canon Dr Ed Newell, chaired the conversation. He was joined by three guest panellists:

- Robin Christopherson – Head of Digital Inclusion at AbilityNet

- Shabira Papain – Head of Diversity, Inclusion and Reach at NHSX

- Lauren Razavi – Writer, speaker and strategist.

As author of the recently published Digital Inclusion: Bridging Divides Cumberland Lodge Report, I attended the webinar eager to hear the panellists’ views on its main themes and, in particular, on how COVID-19 is affecting digital inclusion in the UK.

Indicators of digital exclusion in the UK

The term ‘digital exclusion’ refers to when people are excluded from digital technology (i.e., from the use of computers and smartphones) and the relevant infrastructure behind it (e.g., WiFi). As I mentioned in Digital Inclusion: Bridging Divides, two of the key factors that affect digital exclusion are socio-economic background and geographical location.

If you derive from a lower socio-economic background and/or live in a rural area, you are more likely to be digitally excluded than people who do not. There are many reasons for this, including access to the necessary infrastructure, educational support, security concerns and confidence around technology. These were all discussed in the course of the webinar.

Closing the ‘digital divide’ in the UK

The Cumberland Lodge Report explores the importance of the idea of ‘intersectionality’ in trying to combat digital exclusion. Coined by Black critical race theory scholar Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw, in 1989, ‘intersectionality’ is about looking at the overlapping experiences and identities that a group of people have or experience.

For example, along with people from lower socio-economic backgrounds, people from Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities, and disabled people are also particularly vulnerable to being digitally excluded. If you fall into more than one of these categories, the likelihood of digital exclusion increases, and this overlap of circumstances is the ‘intersectionality’.

These interactions take place in systems and structures that are determined by the law, public policy and the media. For example, someone who is British-Indian and middle class is likely to have different life experiences to someone who is British-Bangladeshi and working class, and so looking at ethnic identity as a factor in digital exclusion requires looking at how ethnic background intersects with other characteristics and circumstances.

Education, employment and social connections can all help to reduce the risk of digital exclusion. As well as a ‘top-down’ approach to policy change, led by leaders and public authorities, the Digital Inclusion: Bridging Divides report supports the idea that a ‘bottom-up’ approach is also required, where communities share information and support one another to become more digitally included.

This discussion also highlighted the need for more specific interventions to target people who are the most vulnerable to being ‘left behind’ with technology.

Tackling poverty and WiFi access

The three main speakers in this webinar on digital inclusion in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic were Robin Christopherson, Shabira Papain and Lauren Razavi. During the webinar that accompanied the launch of the ‘Digital Inclusion: Bridging Divides’ report, Shabira Papain suggested that people on housing/council tax benefit should have received free WiFi during the UK’s national COVID-19 lockdown. This is something I personally agree with: I strongly believe that we cannot eradicate the digital divides in our society without first targeting and eradicting the poverty.

Ensuring that there is nationwide access to good-quality data and broadband should be the Government’s responsibility and not be left to private technology companies. Communities need to feel well supported, confident and secure with their infrastructure, and able to access vital services and information.

Introducing greater flexibility

Another idea that emerged from the webinar is that private companies need to be swifter in understanding their consumers’ needs and providing them with more flexible packages. With the rise of ‘on-demand’ TV, households are increasingly likely to use devices other than their TVs, such as smartphones, to watch shows and films. Robin Christopherson called for more companies to provide flexible bundles, where consumers only pay for the Wi-Fi and data.

This concept could also be extended to mobile phone contracts (where consumers are paying high rates for phone calls that very rarely get used, with WhatsApp and Facebook being more attractive (free) alternatives).

The importance of ‘co-design’

Another theme that came out of both the report and the webinar discussion is that ’co-design’ is vital for ensuring that technology is developed appropriately for the communities it is meant to help, and that voices from traditionally excluded communities are listened to.

‘Co-design’ is where you involve the people who will be using a new technology, at every stage of its development, to inform the design and functionality. The Cumberland Lodge Report recommends that this should be universally implemented, by technology companies as well as the Government.

Conducting co-design during the COVID-19 pandemic has not been easy. However, connecting with pre-existing community networks (i.e., religious places of worship or non-profit organisations) is a useful way of connecting with particular groups of people.

Additionally, using an inclusive platform with this is key. For example, video-conferencing tools that are free to download and use can be used on a smartphone as well as a laptop/computer, and a dial-in option for people who choose to use the telephone conferencing option is also important.

Retaining non-digital options

Despite the general push to develop a more digitally inclusive society, there should still be parity between face-to-face pathways and digital pathways to access services and information.

People need to be provided with choice, and changes should be made at the appropriate pace for them. For example, whilst debit and credit card payments (including contactless payments) are increasingly popular – according to a UK Finance Report published in 2019, 7.4 billion contactless payments were made in 2018 – cash payments are continuing to decline.

This has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, where cash payments were either banned or strictly limited in the UK at the height of the initial crisis. However, it is important to think about the impact this has on more digitally excluded groups, such as the elderly, who may lack the confidence or ability to use cards and who rely solely on cash. The guest panellists called for this to be given greater consideration.

COVID-19 and remote working

There was an agreement amongst the panel that working from home was a trend set to stay, post COVID-19, to a greater or lesser extent. For some, it will no longer be a ‘work perk’; rather, it will become the ‘status quo.’

The advantages of working from home include widening participation, thereby allowing some people (e.g., caregivers and disabled people) the opportunity to work in industries or organisations they might previously have been excluded from. However, there will also be challenges, such as ensuring that people have an adequate digital infrastructure in place to work from home efficiently, and chances to interact meaningfully with, and learn from, colleagues

According to Lauren Razavi, a ‘blended approach’ is most likely to be encouraged and implemented, where individuals can spend a part of their week in the office and the rest at home. Additionally, when people do commute into the office, they may be commuting into a ‘local’ ‘workhub’, as opposed to a big city-centre office.

Remote working does not have to include simply working from home; it could also include ‘working from anywhere’. Individuals could potentially spend several months of the year in another location. An example of this being encouraged was seen when the Prime Minister of Barbados announced a ’12-month Barbados Welcome Stamp’ visa, whereby citizens from other countries, who meet certain conditions, can obtain a visa and work remotely in Barbados for up to a year. Initiatives such as this could be beneficial for the employee, as well as the host country’s economy and tourism industry.

Nevertheless, it is important that new levels of inequality are not inadvertently created as a result of the working from home phenomenon. Employees, including, for example, people with caring responsibilities, need to be supported and listened to, in order to ensure that they are not disadvantaged by the change in work location.

Concluding thoughts

I thoroughly enjoyed this webinar and felt that we could have spoken about digital inclusion all day. Within the hour, the panellists were able to have a varied and stimulating discussion, in front of a public audience joining via Zoom. They each came from different professional backgrounds and brought their own views on the Cumberland Lodge Report’s key themes and implications.

Clearly, there is still a lot of work that needs to be done in our society to reduce digital inequalities, particularly in a COVID-19 world. But with the support of cross-sector organisations, effective collaborations, and robust infrastructure in place, I believe that digital accessibility for all is possible to achieve.