International research collaborations can be fraught with tensions. Unequal power relationships, intercultural misunderstandings and perceived identities have to be navigated by researchers and participants.

Discussions on decolonising global health and research methods have become increasingly prominent and widely debated. On the one hand, advocates for stronger decolonial approaches argue for greater representation, equity, and justice in the field. Others question the rhetoric and tokenistic nature of some of these efforts. Central to these discussions is the importance of reflexivity and critical self-reflection among global health researchers working in contexts they are not native to.

Our Cumberland Lodge Fellow, Sali Hafez, and her research collaborator Diyan Muhsin, reflect in this blog on how they have worked together to overcome some of the obstacles to intercultural aspects of international research.

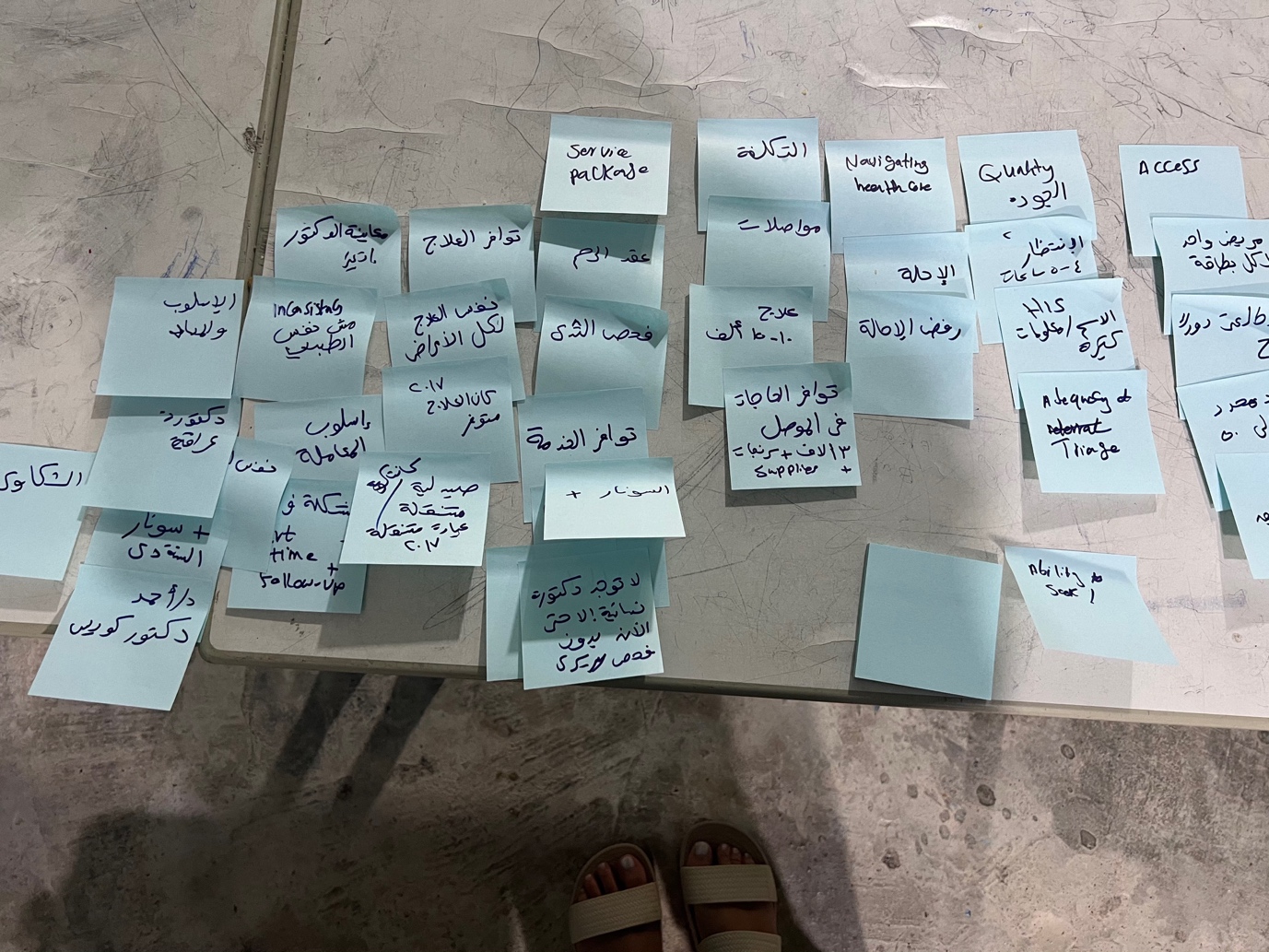

During my data collection in Kurdistan, Iraq, I was constantly reflecting on how I was perceived as a foreign researcher by my Kurdish collaborators. Here, I will share some of the insights I gained from conversations with Diyan Muhsin, Director of Research at the Barzani Charity Foundation (BCF), during our daily trips to the camps in Erbil and Duhok. Our discussions explored a range of topics, including her experiences with foreign researchers, her perspective on what constitutes good research, and her vision for ideal research partnerships.

Diyan highlighted the value of collaboration with foreign researchers, emphasising their diverse knowledge and skills. These collaborations can foster new ideas, facilitate learning from different contexts, and provide opportunities for knowledge exchange and exploration of new tools, analytical frameworks, and schools of thought. However, she also acknowledged the challenges that can arise in these partnerships. One key concern is the power dynamics at play, particularly when foreign researchers may not have a deep understanding of the local context. Diyan emphasised the importance of researchers being aware of their positionality and how it may influence their research.

“Introducing Kurdish identity and culture is part of my everyday job,” Diyan explained. She noted that researchers come from different backgrounds and may have varying levels of knowledge about the region’s political and ethnic complexities. Additionally, some researchers may be more self-reflective about their positionality and how it shapes their understanding of the context.

We frequently discussed the role of local organisations in providing cultural depth and understanding to the research context. This can sometimes be at odds with the ‘foreign gaze’ that researchers may bring. Diyan emphasised the importance of researchers understanding what is baseline and range for communities’ behaviours. She elaborates:

“Some foreign researchers don’t understand what’s normal in the communities they research. Ownership is practised differently and defined differently. They may not be able to differentiate between what’s a perceived reality, and reality.”

Another area of discussion was the principle of mutual benefit for local organisations hosting foreign researchers. Diyan explains the importance of researchers considering the value they can bring to local organisations and avoiding an extractive approach. She expressed a desire for more joint capacity building, closer engagement with researchers to inform programmatic changes, and involvement in community activities.

When asked about an ideal partnership between Kurdistan-based organisations and foreign researchers, Diyan emphasised the importance of long-term engagement, genuine exchange, and mutual benefit. We discussed the idea of ‘parachuting’ researchers who come to the country, collect data, and leave without making a lasting contribution.

Reflecting on my own research and practices, I was struck by the potential for an extractive approach and questioned whether my research was truly providing mutual benefit. As a doctoral candidate, I was eager to contribute to my host organisation but also faced limitations in terms of time and resources. To address this, I committed to translating my research findings into Kurdish, producing a policy brief and a report in both English and Kurdish. This would enable local organisations to use the findings to inform their programming and policies.

I also reflected on the international research impact frameworks that often prioritise the dissemination of findings to global academic audiences with little emphasis on the commitment to sharing results with local participants and organisations. Promoting the utility of globally delivered research requires a stronger emphasis on local ownership and mutual benefit.

In conclusion, I invite foreign doctoral researchers conducting international research to reflect on the complexities of their positioning. Discussing and reflecting on issues of decoloniality, gaze, mutual benefit, and local ownership are key to epistemic justice. By recognising the power dynamics at play, and actively working to address them, researchers can contribute to fostering equitable and meaningful research impact and research utilisation.

Read more posts on the Cumberland Lodge Blog.